Common Ground on Uncommon Ground.

Christian Kolouch

University of Pennsylvania

Candidate one: “Our nation’s infrastructure is collapsing, and the American people know it. Every day, they drive on roads with unforgiving potholes and over bridges that are in disrepair. They wait in traffic jams and ride in railroads and subways that are overcrowded. They see airports bursting at the seams…”

Candidate two: “We have a country that needs new roads, new tunnels, new bridges, new airports, new schools…” “Our airports are like from a third world country…You land at LaGuardia, you land at Kennedy, you land at LAX, you land at Newark, and [then] you [go into] Dubai and Qatar and you see these incredible ― you [go into] China, you see these incredible airports…”

A Thread of Shared Concern

In essence, the two statements above convey a shared belief delivered by assumedly opposed candidates: here, they both insist that due to neglect, our country’s infrastructure has eroded and that there is a resounding need to address the issue via various renovation projects. In their own terms, they identified the same problem, discussed it in a similar situation, and assured whoever was listening that they were each uniquely qualified to address the issue. Importantly, at the time of these statements neither candidate had fully articulated their plan to solve the problem, meaning that the public was being asked to base their particular allegiance on mutual recognition of the expressed concern and also on an individual belief in the person expressing this concern.

Furthermore, as the election season wore on, at various turns, both candidates successfully, similarly spoke about the growing sense of disenfranchisement in the United States, a national need for jobs, a desire to bolster and regenerate the middle and working class, and a certain need to curtail the perceived corruption in Washington. They said similar things and espoused certain, somewhat similar views, yet their messages resonated with purportedly opposed portions of the voting public. Now, if the resonance of the candidates’ views is an indicator, many of us, even across party lines, while transgressing other assumed cultural divisions, saw similar problems and sought similar solutions, identifying with one another’s view point whether we knew it or not.

However, more than ever, we are told, or we may have even come to believe so on our own, that divided we stand, never further apart, shattered into homogenous enclaves of similar thought pejoratively labeled as echo chambers, in which we, in a multitude of voices, effectively speak to ourselves.1 Yet, when looking at the above example - albeit a bit of a simplification - we can see, if we are willing to admit, that despite the apparent chasm between our own and others’ beliefs, somewhere through the muck and mire there still stretches threads of shared concern.

Boiled to a Binary

Muddying the existence of these common concerns however, just as it occurred during the recent election, every two to four years, the American public is tasked with the difficult prospect of choosing sides in order to cast their votes, basing their decisions on apparently opposed platforms. This means that the entirety of the drawn out electoral season (debates, campaigns, plans, promises, ads, platforms, scandals, lapel pins, and catchy barbs) is forced into a single box – two boxes really – one which the voter checks and the other, which the voter leaves blank. Effectively then, the voter (their entire history, ideology, and psychology) and the electoral season itself, are confined to a Yes or No. Though helpful in lubricating the electoral machine, most of us, as individuals, are lost to the reductive event; our nuance and complexion sacrificed, ideally, to the ordered flow of the greater good, but definitely to the binary nature of our choice. Of course, there does exist third party options to choose from, but as it stands, those options seem to be little more than outlets for fringe dissatisfaction. Therefore essentially reduced to a check or not - advocacy or opposition – the subtleties residing in our political beliefs, like the areas of shared concern, often go unnoticed.

This dichotomous process also governed the debate surrounding the Common Core State Standards, a debate that basically forced interested parties to either support or oppose the issue, regardless of positional nuance. Boiled to a binary, interested parties had to either be for or against, advocating or opposing, the dualistic prospect once again implicating the existence of stark divide. Yet, if thought about in a particular manner, there was, much like there was in the debate between Presidential candidates, an assumedly shared concern fueling the majority of involvement in the overall debate: the desire to adequately educate American children in ways that help them live happy, fruitful lives. With the same possible end goal in mind then, opposing sides came to conflict, a conflict exacerbated by the dichotomous demands of the argumentative process. This of course resulted in a tense conversation, subjugating any common desire to the reign of opposing sides, forcing all involved to reduce their position, even person, into one of two categories. And once these categories were created (breaking it all down to either for or against), if left unexamined, they edified the appearance of division. However as mentioned above, if the two positions are probed, this division becomes more difficult to discern, possibly revealing that there was no division at all, but simply differences in the ways participants' minds received, processed, and articulated information – differences that in my opinion, lead to misunderstanding or misinterpretation rather than genuine dispute.

Seeing Eye to Ear

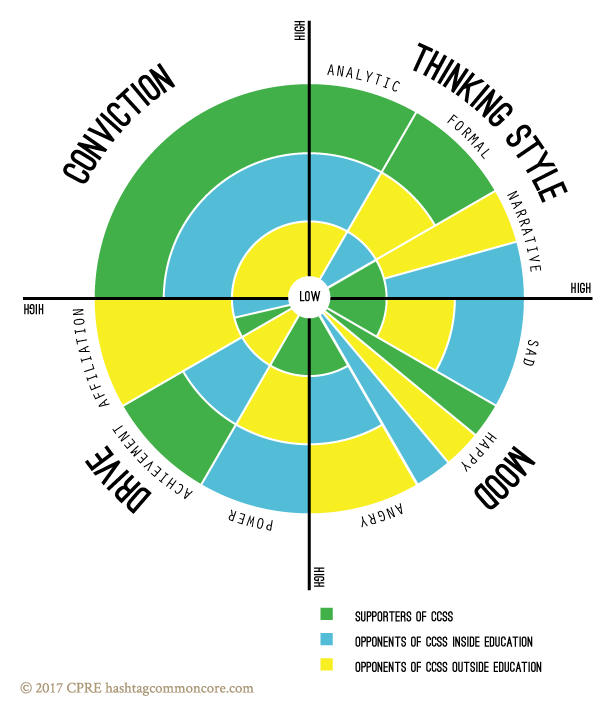

Our Lexical Tendencies analysis was an effort to probe the depths of this binary. By examining the different word types people habitually used while conversing about the Common Core on Twitter, we were able to measure certain aspects of their psychology. Stethoscopic in a sense, word counting allowed us to efficiently plumb a large amount of data in a relatively short period of time, which in turn provided us measures for the author’s moods, drives, thinking styles, and finally, their levels of conviction. With over 100,000 participants and over half a million tweets to sift through, this was a very effective and empirically grounded means to quickly identify various aspects of the psychology working through the CCSS debate.

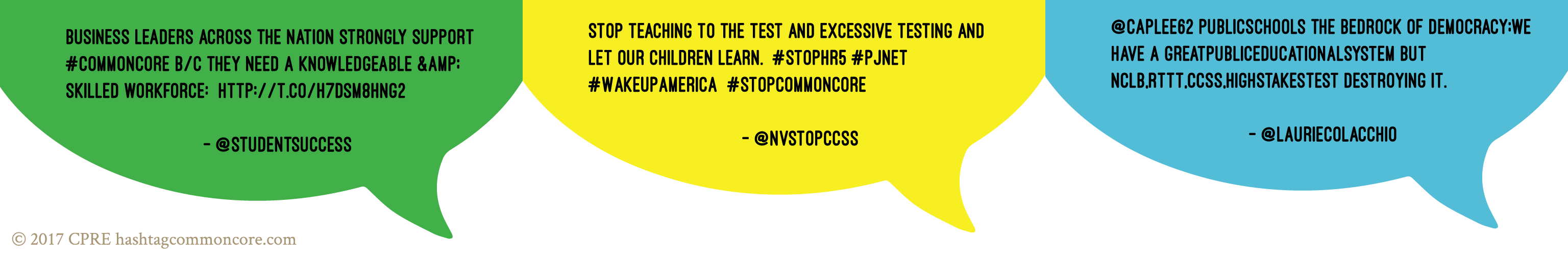

Specifically, our Thinking Style analysis measured the ways in which participants received, interpreted, and articulated information (their position in the debate). Based on the habitual use of certain word groups, we found that each faction had a distinct style of thought and when recalling the definitions of the three measured types, certain insights come to light: Analytic thinkers (in order of their analytic word use from highest to lowest – Green, Blue, and Yellow) understand the world through division and distinction, finding ways to group and order people, places, and events into separate categories of their own design or selection. Narrative thinkers on the other hand (in order of their narrative word use from highest to lowest - Yellow, Blue, then Green) interpret information through stories and focus their thoughts on the individual experience. They understand the world and express themselves through anecdote, seeing life occur at the personal level. Finally, Formal thinkers (in order of their formal word use from highest to lowest - Green, Yellow, then Blue) are stodgy and emotionally distant; often believed to be arrogant, they communicate in structured, dry clips, using hifalutin language and rigid argumentation.2

Much like the differences in audio vs. visual or visual vs. tactile learners, the different thinking styles are prone to absorbing and sharing information in distinct manners, inferring that information interpreted and presented in different ways has the potential to be dismissed, lost, or misunderstood. For example, if a formal thinker, in their slightly pretentious, almost dismissive manner, only understands or legitimizes the arguments of those who communicate and think like them (not necessarily ratifying or arguing against the actual content of the arguments put forth) is in a debate with a narrative thinker, the arguments and concerns of the opposing party risk going unaddressed. In this example, the dismissal would not be a result of the content, but instead due to the mode of presentation and possibly earlier interpretation. Expressed in another way, if a narrative thinker communicates and thinks in stories, the narrative thinker might dismiss or stand against the necessarily analytic aspects of the CCSS debate, interpreting the parsed categorical or numerical analysis as a dehumanization of the parties involved. Again, perhaps it is not the actual information that the narrative thinker opposes - the gathering of added context - but more the manner in which this process has been described and advocated for, something that if restructured to better fit the thinking style of the recipient, might be more readily received.

We saw reflections of this misunderstanding throughout the conversation, but specifically so in one of the primary contentions to the CCSS: the data mining tied to the Common Core. Many people on the opposing side frequently expressed a clear concern that data mining would dehumanize education and turn children into troves of information to eventually be scoured for profit or other nefarious purposes. This interpretation was particularly common amongst the narrative-minded yellow faction, people who saw the issue as a personal one, their common contention to the data mining not about a specific standard, but instead about their understanding of this secondary point. On the other side of the problem stood green: the faction scoring highest on our analytic measure, a group of people who generally interpreted the data mining in a much different manner. As advocates for the process, they believed it to be an integral way to further understand education, the resulting information providing insight that the individual student experience could not. Interpreting this point in different ways, they communicated about this point in different ways, possibly revealing that interpretation and communication rather than specific CCSS content was the issue. Furthermore, being that their view points aligned with their thinking styles, we can begin to ask about the true roots of the conflict, asking if it might have been a cognitive issue rather than a substantive one? And if this is the case, taking this idea one step further, are we, generally speaking, neurologically built to misunderstand certain types of people?

We saw reflections of this misunderstanding throughout the conversation, but specifically so in one of the primary contentions to the CCSS: the data mining tied to the Common Core. Many people on the opposing side frequently expressed a clear concern that data mining would dehumanize education and turn children into troves of information to eventually be scoured for profit or other nefarious purposes. This interpretation was particularly common amongst the narrative-minded yellow faction, people who saw the issue as a personal one, their common contention to the data mining not about a specific standard, but instead about their understanding of this secondary point. On the other side of the problem stood green: the faction scoring highest on our analytic measure, a group of people who generally interpreted the data mining in a much different manner. As advocates for the process, they believed it to be an integral way to further understand education, the resulting information providing insight that the individual student experience could not. Interpreting this point in different ways, they communicated about this point in different ways, possibly revealing that interpretation and communication rather than specific CCSS content was the issue. Furthermore, being that their view points aligned with their thinking styles, we can begin to ask about the true roots of the conflict, asking if it might have been a cognitive issue rather than a substantive one? And if this is the case, taking this idea one step further, are we, generally speaking, neurologically built to misunderstand certain types of people?

What Fuels Our Perceptions and Misperceptions Alike

In another Lexical Tendencies analysis, we measured the Drive Orientation of the participating factions and found that each group was distinctly driven in one of three ways – by Power, Achievement, or Affiliation. To quickly refresh your memory, or if you have yet to read the analysis, power people have an innate drive to create order by organizing people and situations into coherent groups or events. Achievement oriented people on the other hand are focused on goal-oriented success, ideally receiving stature or recognition in return for their efforts. The final drive orientation is affiliation wherein folks are driven by the development and maintenance of harmonious relationships, seeing situations as means to affiliate with others or as interactions between affiliated groups.3 Importantly, there is no hierarchy of merit to any of the three drives. They are each of equal value and all can be used for both good and bad. To further understand the meaning of each drive, it is also integral that we remove any personal connotations we’ve attached to the attending terms. Being driven by power for example does not necessarily produce negative results, nor infer a tyrannical want for control; in fact, power people are often very generous, considerate, participating members of society who generate net positive effects on those around them.

With these ideas understood, like our Thinking Style analysis discussed in the previous section, this measure was also based on linguistic tendencies extrapolated over a faction’s cumulative participation in the CCSS Twitter conversation, revealing habits of writing that in turn revealed habits of mind. For example, our drive analysis revealed that the group’s comprising the Common Core opposition - separated into the blue and yellow factions - (blue – opponents within education and yellow – opponents outside education) were multifaceted in their shared position, each position motivated by a different drive. Though they agreed in their stand against the CCSS, they apparently did so for very different reasons, showing that division existed on the same side of the debate.

The blue group was measured as being motivated by power while the yellow group measured highest on the affiliation drive. As we mentioned, in our results, these measures revealed a very important nuance in the oppositional stance. There, we postulated that  blue’s measure on the power drive opened the possibility that their faction may have perceived the CCSS as a power issue. As a group comprised of people inside education, their concerns over power could be inferentially connected to their fears regarding the Common Core's effect on educator agency. Simply put, it is possible that they used power words because their power drive was threatened, thus activated, by a potential threat to their power in classrooms and schools – remember power here means to order and organize, ordering and organizing a classroom or school, something that could have been uniquely disrupted by the standards. There is strong evidence to suggest that because they were oriented in a certain way, educators perceived the situation in a certain way, and therefore specific concerns arose due to their effect on the driving orientation.

blue’s measure on the power drive opened the possibility that their faction may have perceived the CCSS as a power issue. As a group comprised of people inside education, their concerns over power could be inferentially connected to their fears regarding the Common Core's effect on educator agency. Simply put, it is possible that they used power words because their power drive was threatened, thus activated, by a potential threat to their power in classrooms and schools – remember power here means to order and organize, ordering and organizing a classroom or school, something that could have been uniquely disrupted by the standards. There is strong evidence to suggest that because they were oriented in a certain way, educators perceived the situation in a certain way, and therefore specific concerns arose due to their effect on the driving orientation.

On the same side of the debate, but driven by a much different cause, the yellow group measured highest on the affiliation measure. Our postulation in this case was that, as shown by their lexical tendencies, the yellow group’s opposition to the CCSS was focused on how the reform might affect the relationships they knew, the relationships  they had formed, and the relationships they hoped to maintain in, around, or through their schools, including their relationships with their own kids. In this case, members of the yellow group used affiliation words because they were concerned about their affiliations; their participation in this debate, motivated by a desire to maintain or protect academic relationships they had formed. A potential example of this concern was the oft-voiced fear that the CCSS would impede local control of education - the local nature of the education process, providing the possibility for maintained relationships within given locales. If the CCSS, as commonly interpreted, was a national intrusion on local power, it could be perceived that the centralized environment would create relational barriers in a given school or district. Rationally speaking, it is difficult to form or maintain a relationship with someone working in an office in Washington D.C. when that person lives in Idaho or Ohio; while conversely, having an impactful relationship, with people in your local district or school,

they had formed, and the relationships they hoped to maintain in, around, or through their schools, including their relationships with their own kids. In this case, members of the yellow group used affiliation words because they were concerned about their affiliations; their participation in this debate, motivated by a desire to maintain or protect academic relationships they had formed. A potential example of this concern was the oft-voiced fear that the CCSS would impede local control of education - the local nature of the education process, providing the possibility for maintained relationships within given locales. If the CCSS, as commonly interpreted, was a national intrusion on local power, it could be perceived that the centralized environment would create relational barriers in a given school or district. Rationally speaking, it is difficult to form or maintain a relationship with someone working in an office in Washington D.C. when that person lives in Idaho or Ohio; while conversely, having an impactful relationship, with people in your local district or school,  unmitigated by national standards, is assumedly easier to maintain.

unmitigated by national standards, is assumedly easier to maintain.

All told, on the same side of the argument, the members of the blue and yellow factions shared a common concern, yet they were propelled by different drives, coming together to achieve a common goal while not letting their personal interpretations or motivations impede the success of their shared desire. They were divided, yet solid, inferring that division does not, paradoxically, inhibit cohesion; in fact, that divisions of any kind can be overcome when efforts are directed toward identifying and focusing on shared concerns. In this case, there was a situational division between the blue and yellow group – one faction outside education and the other inside education - yet, the two were able to overcome this difference with the same end goal in mind. I don’t believe they did this knowingly, however it does reveal the possibility that our cultural divisions do not prevent us from addressing common concerns. So, if we are really living in a fractured country, as has become round belief, there still remains plenty of common ground on which we can meet and arrive at mutual goals.

A Defined Moment in Misperception

On the other side of harmony however, within the same Drive Orientation analysis, we located further evidence of misperception and miscommunication. As the highest measuring faction on the achievement drive, the Green group, used the language found in the Common Core itself - language also found in our achievement word library – to advocate for a system that promoted achievement. Fundamentally, the Common Core was an achievement or performance-based reform, requiring teachers to turn the education process into a defined series of steps, the landings of which, were various  standards that need be met by students and teachers alike, in order to continually climb or achieve. Because it made sense to them (the reform a reflection of their dominant drive) the green group used arguments and language which expressed an achievement view of education: education as a means for ascension, something meant to promote or encourage success. Such a fact illuminates the reality that the standards were created (and advocated for) by a group of people who perceived education in a very particular manner that did not necessarily coincide with the educational philosophies of others.

standards that need be met by students and teachers alike, in order to continually climb or achieve. Because it made sense to them (the reform a reflection of their dominant drive) the green group used arguments and language which expressed an achievement view of education: education as a means for ascension, something meant to promote or encourage success. Such a fact illuminates the reality that the standards were created (and advocated for) by a group of people who perceived education in a very particular manner that did not necessarily coincide with the educational philosophies of others.

As we mentioned in our results, not all people consider the primary purpose of education to be about academic or social achievement. In fact, many people view education as a process dedicated to the enriching of a student’s ability to critically think, or alternately, as a means to the creation of a responsible, conscientious public citizenry. The problem with promoting a specific educational view (seeing education as specifically for achievement) is that the use of achievement oriented language may not have necessarily connected with those who have different ideas regarding education's purposes.

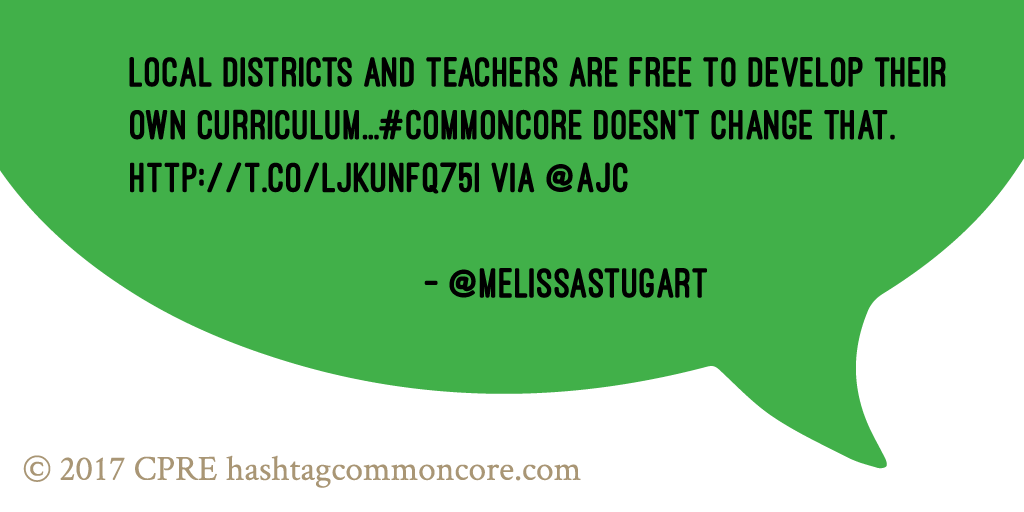

For example, if I see something as a power scenario and I try to convince someone of its merit based on its ability to promote a person’s power, yet that person is not driven by power, my promotion might fail to register or engage my interlocutor’s needs. Affiliation people are not concerned with how a reform affects their ability to order or organize; they are more worried about how a reform inhibits or promotes their capacity to harmonize relationships with others. Such a schism then between rhetoric, position, and reception makes me wonder if the various arguments put forth during this debate had been fervently recast, using different language more focused on alternate views, without actually changing the standards themselves, would the Common Core, and Green’s advocacy, have been met with increased social support? Had they not generally positioned the CCSS as a means to increase achievement, but rather as a conduit for critical thinking or a method to promote teacher autonomy, or even how it could engender harmonious relationships in schools, would the debate have been less contentious? To green’s credit, they did just this in the adjacent example, but I wonder if this was too little too late, or maybe just a  reactionary, even, singular example of Green attempting to calm the power fears of Blue?

reactionary, even, singular example of Green attempting to calm the power fears of Blue?

Final Thoughts

All this combined leads me to wonder, what was the real nature of the Common Core conversation on Twitter? Was it in fact a conversation at all, or was the issue merely a template on which people worked out their individual psychologies under the guise of an education reform debate waged over social media? As my colleagues noted in the first #commoncore project, this appears to have been something of a proxy war, a substitute topic co-opted by a multitude of minds, in my opinion, though it wasn’t the means to discuss other political issues, but instead a conduit through which individuals exercised their desires, drives, moods, and angst. The yeses and no’s then, at least in my eyes, eventually were of no matter; removed from the dichotomy of advocacy or opposition, this conversation became something else.

What exactly it was, I do not know, but I can say for certain that it was not a simple matter of for or against, nor a proposition understood by simply counting yeses and no’s. It is so far removed from the binary, that to think of it in these terms further oversimplifies an already oversimplified subject. As shown by the size of this project, and the multitude of ways in which we examined the conversation, this was something much greater than a dichotomous clash - the issue itself, the standards, a mere fragment of the conversation, a focus upon which prevents genuine understanding of what took place. In the same sense, focusing on the sensational aspects of the last election, or the apparently cavernous division between political tribes, derails a person from truly understanding the contemporary political climate - what took place and why things are the way they are – and also possibly causes us to miss the threads of shared concern with which we might mend our national bond.

References

- Bishop, Bill, and Robert G. Cushing.The big sort: why the clustering of like-minded America is tearing us apart. Boston, MA: Mariner, 2009. Print.

- Pennebaker, James W.The secret life of pronouns what our words say about us. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press, 2013. Print.

- McClelland, D. C. (1987). Human motivation. CUP Archive.