The Rise of Crowd-Sourced Political Influence

by Jonathan Supovitz

University of Pennsylvania

Consortium for Policy Research in Education

“The medium is the message,” communication maven Marshall McLuhan wrote in 1964, explaining that the means of communication can be even more important than the message it carries.1 Twitter fits this phrase aptly. Founded in March 2006, some 40 years after McLuhan’s famous utterance, the social medium has grown to over 500 million users worldwide in just over seven years. And we should not think of Twitter as just one entity, because it hosts a multitude of social networks along a plexus of pathways by which users communicate about a vast range of topics. As such a potentially potent resource for connecting people together, Twitter (and other social media like it) raises essential questions about how these technology-enabled social network platforms are changing the practice of politics that initiate and sustain (or not) public policies.

Our investigation of the public debates on Twitter focused on social activism around the contentious Common Core State Standards education reform initiative in the United States. We examined Twitter data from a six month period from September 2013 to February 2014, which contained 190,000 tweets from 53,000 distinct actors. Through our analyses, we examined what the larger Twitter social network looked like over this time period, how the Common Core was viewed by Twitter activists, who were the major players and who they communicated with (i.e. the social networks), and how people communicated (i.e. the language tweeters used). In this essay, I focus on how social media-enabled social networks are changing the discourse in American politics that produces social policy.

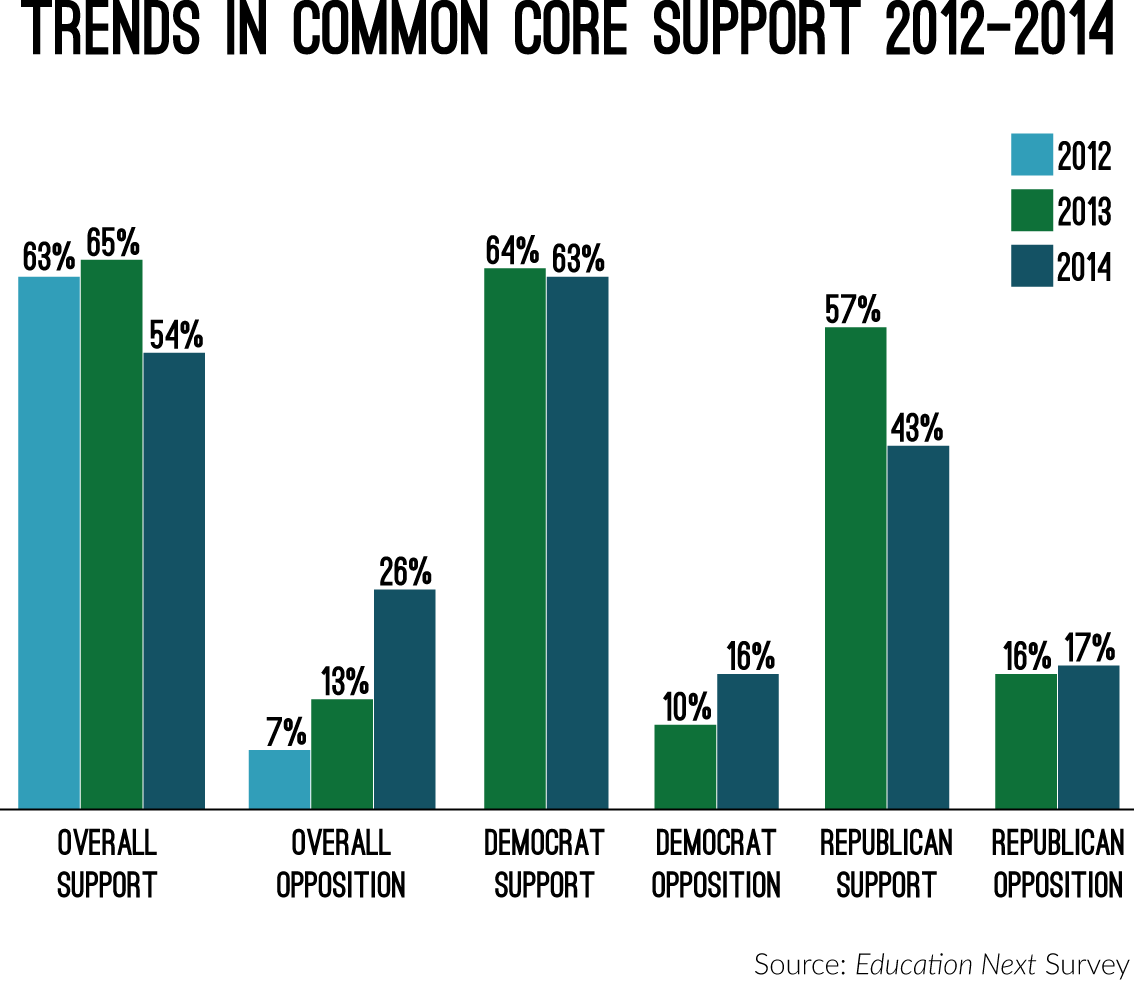

Let’s start with the question of influence. There can be no doubt that the Common Core State Standards, adopted with bipartisan support in 2010 in 46 of the 50 states, have become one of the most contentious issues in education today. As one sign of this, longitudinal surveys from Education Next indicate that a 9-1 support ratio in 2012 dropped to 2-1 in 2014. In addition, the decline in support cleaves along political party lines; while Democrats continue to support the Common Core by a 4-1 ratio, Republicans are evenly split.

The six-month period we examined in this study occurred in the midst of this precipitous slide in support for the Common Core. During this time there was a steady drumbeat of communication on Twitter about the Common Core, much of which we have documented on this website. Overall, almost 53,000 individuals and groups used the #commoncore hashtag during this six month period and volume averaged more than 30,000 tweets per month. [We continue to track activity on #commoncore, and the volume, as of December 2014, continues to average about 40,000 tweets per month, which indicates that the Common Core continues to be a hot education topic.] So what can we say about the connection between all this Twitter conversation and broader public opinion about the Common Core? Is it just coincidental that the Twitter conversation was rabid at the same time that public opinion was dropping? And how does this affect political decisions, policymaking, and implementation?

Is Twitter an Arena for Democracy, an Echo Chamber, or an Incubator for Influence?

During the six months that we closely monitored tweets, some high-profile Common Core-related events occurred, causing spikes in #commoncore activity. These are described in Content of the Tweets in Act 3. Some of the highest-profile events included:

- In September 2013, the state of Florida, which was the fiscal agent and founding state for the federally funded and Common Core-aligned Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) withdrew from the testing consortia.

- In November 2013, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan made his infamous comment: “It’s fascinating to me that some of the pushback [against the Common Core] is coming from…white suburban moms who—all of a sudden—their child isn’t as brilliant as they thought they were and their school isn’t quite as good as they thought they were, and that’s pretty scary.”2

- In February 2014, Bill Gates wrote an editorial in the USA Today trying to dispel some of the myths around the Common Core, which he called “the best way to fix school for our kids.”3

- Also in February 2014, Dennis Van Roekel, the president of the National Education Association (the largest teachers’ union in the United States), called for a course correction of the “botched implementation” of the Common Core.

Each of these incidents attracted huge attention on Twitter as well as in the popular media and played into a growing perception of the Common Core as a beleaguered education reform. But the incidents were also important because they helped create and play into a particular narrative, forming the themes in our analysis of the Twitter data.

By leaving the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) assessment consortia - for which it was the fiscal agent, no less) – Florida became one of the first states to act on within-state opposition to the Common Core. This action emboldened politicians (largely, but not solely, Republicans) in other states to oppose the Common Core and reverberated in places like Indiana, which dropped the Common Core in April 2014; in Louisiana, where Governor Bobby Jindal and 17 legislators sued the State Board of Education to stop Common Core implementation; and Michigan, where the state senate overcame some tense moments before voting to continue to use state funding on Common Core implementation.

Duncan’s gaffe was important for two reasons. First, it perpetuated connections between the Common Core and the federal government’s role in education. While the creators of the Standards were careful to point out that the National Governors Association (NGA) and Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) were its sponsors, the federal government had used the substantial resources of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) and Race to the Top (RTT) funding to provide incentives for states to adopt the Common Core and funded the development of the two Common Core-aligned tests. All these events contributed to the perception that the federal government sponsored the Common Core State Standards. Second, Duncan’s awkward comment reawakened fears about drops in performance when the results of the first Common Core tests are released in the summer and fall of 2015. Would middle-class Americans, who consistently rate their own child’s school as above average, be so shocked by drops in performance that they would press for a pull-back of the raising of performance expectations that reduced tests scores would imply?

Bill Gates and his foundation have come to represent the business interest in education, leaving many suspicious because they fear profit-seeking will trump the public good. Gates has become a magnet for Common Core opposition because the Gates Foundation has spent over $200 million on Common Core support and advocacy.4 Even though the Gates Foundation and Microsoft are distinct and separate entities, many opponents view these dollars as an investment in the education technology market where a range of vendors are sure to profit as educational and testing resources are increasingly available on-line.

Finally, Van Roekel’s comment reflected an increasingly tense relationship between teachers and the proponents of the Standards. Initial widespread teacher support for the CCSS has become muddied by conflation of standards implementation and teacher evaluation, particularly in states which received federal RTT funding, and by teacher frustration with both the increase in testing and the misalignment between old tests and the new standards.

Thus, each of these events poked a sensitive nerve in the soft underbelly of education reform.

Yet these events, even while reverberating throughout the Twittersphere, were also national stories in the mainstream media in their own right. Florida’s announcement, made by Governor Rick Scott, was sure to garner national attention. Duncan’s suburban mom comment was covered in the Washington Post5, MSNBC6, and Politico7. New York Times editorialist Frank Bruni8 wrote a column about it. Bill Gates’s editorial in USA Today, dropped in front of many a hotel room door in America on that cold February morning, was intended for a broad audience.

The interrelationship between social media and the popular media, however, remains ambiguous. Just what is the directionality of influence? Are beliefs being fomented on social media and moving out into the mainstream? Are ideological segments of the popular media (FoxNews, MSNBC, Bill O’Reilly, Glenn Beck) feeding stories into Twitter both directly and through their followers, which are then tweeted and retweeted out across the social networks, taking on different interpretations as they go, like the old chain game of telephone? Are the same events and issues refracting out through all forms of media more or less simultaneously, with each subgroup interpreting them with their own lens and reporting them with different tenors for different ideologically inclined audiences? Is social media influencing mainstream opinion? Is sub-stream opinion influencing social media? Both?

In our analyses of #commoncore we found evidence for at least three explanations that help to make sense of how the cacophony we observed on Twitter might be working its way to influence public perceptions. The first possible interpretation is that Twitter is a distinct venue where people debate ideas to decide their positions on the merits – an arena of democracy. There are numerous examples in the tweets where two or more people were not just parroting others’ views, but mentioning each other and have a discussion about a Common Core-related topic. Further, in interviews, some of the elite actors talked about discussions they had via Twitter in which others that influenced their views.

A second possible interpretation is that Twitter is an echo chamber where people reinforce the beliefs of those like them to get affirmation for their previously-held views and, in doing so, amplify the prevailing conception. The structure of the three factions that emerged out of the social network analyses in Act 1 provides credence to this notion of homophily, or the tendency of people to affiliate with likeminded others. This is a continuation of the pattern that emerged when cable television grew out of broadcast TV in the 1980s and began to splinter into more specialized political shows catering to particular partisan views (see Evolution of Media in Politics). Similarly, on Twitter, particular groups with similar political convictions tend to follow, retweet, and mention the views of likeminded others.

The third possibility is that the fomentation of debates on Twitter acts as an incubator for influence whereby the buzz from often sensationalized Twitter messages seeps out into larger social networks that connect to public perception. In this view the echo chamber is not hermetically sealed. One piece of evidence for this is the presence of media members in both the transmitter and transceiver networks, who acted as conduits for Common Core information to travel through their own journalistic networks into the mainstream. A second piece of supporting evidence was how interviewees mentioned that their tweets were quoted in mainstream media outlets and that they were sought after to do interviews with the mainstream media. This may even signal the onset of a blurring of the different types and sources of media.

These explanations are also not mutually exclusive and it is plausible that all three of these phenomena are at play simultaneously. Twitter can be an arena for democracy, an echo chamber, and an incubator for influence all at the same time. And perhaps even more importantly, as we are starting to see the ways that the Common Core debate has trended over time, this new mixture of political activism on social media that spurs robust social network activity is changing the way that politics and policy interact.

A New Policymaking Environment?

The interrelationships between politics and policymaking are complex. Coalitions arise around a perceived problem or need in society and foster a constituency to address it. These alliances are often fluid. The priority for any particular action rises or falls due a host of factors, including the grit and determination of key actors, the particular combination of allies, and unpredictable external events and circumstances. In such a milieu, the Common Core State Standards movement arose from the end of the test-based accountability era of No Child Left Behind, the ongoing dissatisfaction with national educational performance, and long-simmering angst over persistent national inequalities and comparative international mediocrity. These factors and others coalesced into the search for the next great policy lever to pull, which turned into a fast-track effort to resuscitate and enhance past standards-based reform efforts. The effort looked like smooth sailing through the early part of the 2010’s, as state after state adopted the Common Core. Since that round of adoption, however, the sea has grown choppy.

In some ways the fractious rabble-rousers on Twitter are a counter-ballast, or even a reaction to, the increasingly slick sheen of professional media advisors and image consultants that have turned public issue advocacy into a business model. We found no single group or entity orchestrating opinion on Twitter. The closest to it was the Fordham Institute’s gang of Common Core supporters, which used a team of Fordham staff (Michael Petrilli, Michelle Gininger, Michael Brickman and their blog (The Education Gadfly) to retweet each other’s tweets. Far more commonly, the pulsing of messages that occurred ubiquitously in all three of the structural factions that made up the #commoncore network were reverberated through loosely affiliated networks of individuals and groups who shared common beliefs, but were not operating in concerted campaigns.

At this stage of the evolution of education issues on social media, the organic nature of Twitter messaging is in sharp contrast to the more coordinated activities of professional advocacy groups on either side of the Common Core issue. While these groups had some presence on Twitter, they were support players in the debates rather than dominant actors. From this perspective, social media-enabled social networks bring a new dynamic so the factional tussle for influence in American politics and policymaking.

The influence of factions, and the advantages this splintering produces for special interest groups in shaping public policy, is as old as the nation. In 1787, writing under the pseudonym Publius, James Madison wrote Federalist Paper #10, which acknowledged the importance of factions in vigorous public debate, but grappled with how to control their tendencies to seek domination at the expense of the public interest. For Madison, the checks and balances built into the American system were at least in part due to his conclusion that “…the causes of factions cannot be removed and that relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its effects.”9 As America has long protected the right of factions to advocate in American politics, it has also struggled to limit their supremacy over the policymaking process.

Most of the recent attention to factions seeking to influence policymaking has come in the form of debates about the increasing role of money in politics. We all know how important money is to trumpeting a message. In fact, the main critique of the Gates Foundation in the #commoncore network is their contribution of $200 million to support Common Core advocacy groups and public information campaigns in a variety of ways.

But another important lesson from our analysis of the Common Core debate on Twitter is that that social media-enabled social networks are an increasingly potent force for gaining the attention of policymakers both by communicating to them directly and by raising enough noise and attention through crowdsourcing grassroots energy to influence both media coverage and public opinion that gains their attention. The prime examples of the rapid ascent of grassroots organizations active in the #commoncore network which have no infrastructure and are entirely run by volunteers are the Bad Ass Teachers Association, which in two years has accummulated 39,000 followers in 50 states and is run by 245 volunteers; and Red Nation Rising, which accrued some 37,000 followers in its first six months and claims to have made nine billion social media impressions. These groups arose with no money and no organization other than a volunteer social media manager who tweets from her phone. Based upon the entire #commoncore social network and these vivid examples, I argue that social media- enabled social networks are shifting the dynamics of factional politics in American policymaking.

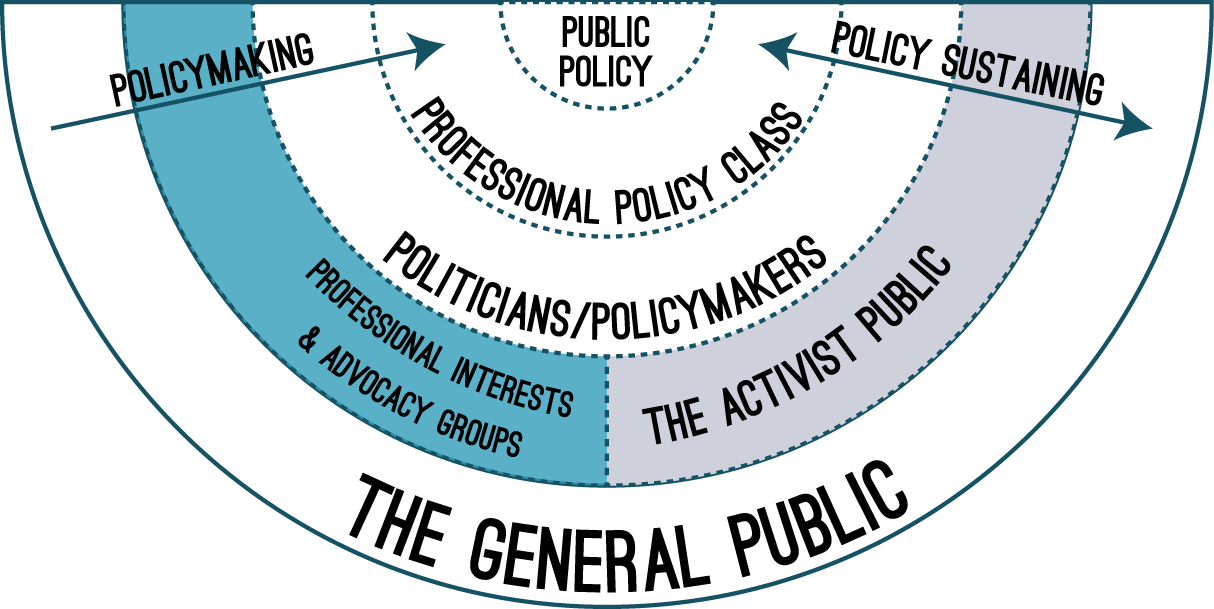

In the figure to the right, I depict the different groups that contribute to making public policy, at the center of the image. Layered closest to policy are professional policymakers, who may be policy staffers, or career legislative assistants who actually craft the details of a policy itself. Depending on the complexity of the policy, this group may or may not play a major role in policymaking. Adjacent to them are politicians who, once elected, are the creators of policy. The next (shaded) ring, contains advocates who either support or oppose a policy, or who desire a particular rendition of a policy. I have highlighted this ring because it contains the main actors of the #commoncore story, and I will return to it in a moment. The final ring of the semi-circle is the general public. The rings are depicted as dotted lines to signify that the relationships and flow of information among these layers of the process are porous. All of these rings together contribute to the policy making process, for they all exert pressure and inform the development of policy in different ways and by different means.

In the figure to the right, I depict the different groups that contribute to making public policy, at the center of the image. Layered closest to policy are professional policymakers, who may be policy staffers, or career legislative assistants who actually craft the details of a policy itself. Depending on the complexity of the policy, this group may or may not play a major role in policymaking. Adjacent to them are politicians who, once elected, are the creators of policy. The next (shaded) ring, contains advocates who either support or oppose a policy, or who desire a particular rendition of a policy. I have highlighted this ring because it contains the main actors of the #commoncore story, and I will return to it in a moment. The final ring of the semi-circle is the general public. The rings are depicted as dotted lines to signify that the relationships and flow of information among these layers of the process are porous. All of these rings together contribute to the policy making process, for they all exert pressure and inform the development of policy in different ways and by different means.

The uni-directional arrow on the left of the image indicates that policy making usually moves towards the center. While it may not start with pressure from the general public, it is usually interest groups that are pressing on politicians which results in the development and enactment of policy. While there is certainly back-and-forth in this process, the forces that produce policy generally move toward the center. The bi-directional arrow on the right of the image represents the fact that, once a policy is made, the process does not end. The constant agitation against enacted policy—made far easier by social media--means that no policy is safe from modification or elimination.

Returning to the shaded ring, which consists of professional interest groups, advocacy organizations, and increasingly with what I call “the activist public.” The activist public includes those individuals and grassroots organizations who have gained increased visibility and influence in the social networks on Twitter, as measured by their presence in the elite transmitter and transceiver networks (see Act 2, The Players). The influence of these individuals and groups is based upon how well-connected they are in social space and their ability to use social media to spread their views. There are many examples of these actors in the #commoncore network, including many of the individuals and organizations who are active on Twitter in all three structural factions (the yellow, green and blue factions discussed in Act 2). Examples of individuals include professional educators like DG Burris, Peter Osroff, and Tim Farley; groups outside of education like the Tavernkeepers and Red Nation Rising, and groups inside education like the Bad Ass Teachers. These individuals and groups represent a new and vocal set of influencers on the policymaking process who use social media as a democratizing megaphone to amplify their collective voice through their social networks.

The activist public is jostling into the space largely dominated by the professional interests and advocacy groups who have been the primary influence on public policymaking for the last several decades. While professional advocacy groups (like Cato Institute, The Pioneer Institute, The Fordham Institute, the National Education Association, the American Enterprise Institute, the Heritage Foundation, and several state public education funds) are present in the #commoncore network, they are generally less active than members of the activist public. While it is beyond the scope of this project to judge the relative effect on public policy of the professional advocacy groups relative to the activist public, it is clear that the social media-fueled activist public is a relatively new phenomenon in the policy space, and has garnered tremendous attention among both policymakers and the general public. As a supporting anecdote, I have attended several education policy meetings where elected officials and members of the professional policy class have commented on the clarion voice they hear coming from the activist public. So either the activist public is expanding its influence as a faction in education politics or they are elbowing into the space heretofore dominated by professional advocacy groups. Either way, they are beginning to change the dynamics of the political process by which policies are produced and sustained.

As astonishing as the story of the Common Core as told through #commoncore activity on social media may be, it is really just the beginning. Twitter activity is a harbinger of social media’s increasingly powerful influence on policymaking to come. We shall look back upon this as a nascent era of a series of skirmishes across social media-enabled social networks in the cat and mouse game for influence over the messages that help mold public opinion that politicians/policymakers cater to. In this early era, crowd-sourced political influence is acting as a counterbalance against organized and corporate interest-funded advocacy groups. We may soon see the better-established social media sites increasingly hegemonized by more organized professional advocacy interests who seek to use their well-resourced influence to shape opinion. In the ongoing struggle for political influence and advantage, social media-enabled social networks are an undeniable force.

References

- McLuhan, M. (1994). Understanding media: The extensions of man. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Strauss, V. (2013, November 16). Arne Duncan: ‘White suburban moms’ upset that Common Core shows their kids aren’t ‘brilliant’. Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2013/11/16/arne-duncan-white-surburban-moms-upset-that-common-core-shows-their-kids-arent-brilliant/

- Gates, B. (2014, February 12). Bill Gates: Commend Common Core. USA Today. Retrieved from http://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2014/02/11/bill-melinda-gates-common-core-education-column/5404469/

- Vicens, A. (2014, September 4). Bill Gates spent more than $200 million to promote Common Core. Here’s where it went. Mother Jones. Retrieved from http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/09/bill-melinda-gates-foundation-common-core

- Strauss, V. (2013, November 16). Arne Duncan: ‘White suburban moms’ upset that Common Core shows their kids aren’t ‘brilliant’. Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2013/11/16/arne-duncan-white-surburban-moms-upset-that-common-core-shows-their-kids-arent-brilliant/

- Richinick, M. (2013, November 21). Arne Duncan reflects on ‘white suburban moms’ comment. MSNBC. Retrieved from http://www.msnbc.com/morning-joe/sec-education-arne-duncan

- Simon, S. (2013, November 18). ‘White moms’ remark fuels Common Core clash. Politico. Retrieved from http://www.politico.com/story/2013/11/arne-duncan-common-core-comment-99987.html?hp=f3

- Bruni, F. (2013, November 23). Are kids too coddled? The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/24/opinion/sunday/bruni-are-kids-too-coddled.html

- Madison, J. (1787). Federalist 10. The Federalist Papers, 77-84.