Theory of Social Capital

A Relational Perspective

This project is based on the fundamental idea that connections and ties between individuals create a larger network, and that this network is important to outcomes at both the individual and collective level. Ideas, opinions, and information that flow through these ties can be influential and impact behavior.

This is idea is grounded in social capital theory, which posits that individuals exist in a social structure of relationships. This structure of relationships facilitates or inhibits an individual’s access to both physical and intellectual resources such as knowledge, ideas, and opinions. Social capital theorists consider the richness of a social network to be a key component of a group’s social capital, which refers to the kinship, trust, and goodwill that provides a collective advantage to the community.1

Sociologist Robert Putnam has chronicled the social benefits of memberships in organizations such as churches, clubs, and more.2 He hypothesized that the benefits he observed were due to the connections that these groups offer to their members. In another famous example of the importance of social capital, Mark Granovetter found that extended ties even beyond one’s tight-knit circle of friends helped people gain access to job opportunities.3

Historical Grounding

The most explicit and earliest network approach to society dates back to German sociologist Georg Simmel (1858-1915) who wrote, “Society exists where a number of individuals enter into interaction,” and the object of study “was no more and no less than the study of the patterning of interaction.”4

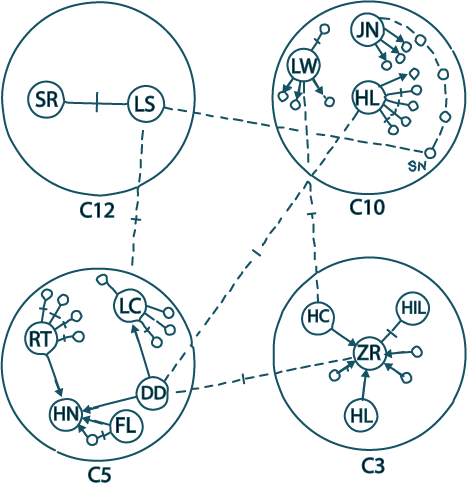

Contemporary social network analysis was formalized in the 1930s with the work of Jacob Moreno, who studied runaway girls and argued that their behavior was influenced by the social links among them.5 Moreover, the girls themselves may not have been consciously aware of how their actions were socially influenced and how, ultimately, it was their position in a social network that may have affected the runaway behavior. This idea is still prominent today and has expanded to the idea that social influence can impact a host of behaviors—both consciously and unconsciously—from happiness to weight gain to access to career opportunities.

Moreno's sketch of the cabins of runaway girls.

Moreno’s early drawings of the cabins in which the runaway girls stayed and the relationships among the girls were some of the earliest depictions of social networks. The larger circles are cabins and the smaller circles depict the initials of runaway girls. The lines represent connections between girls. This was one of the earliest sociograms is an example of state-of-the-art infographics from the 1930s.

Thus, a core idea of the work running from Simmel to Moreno to Coleman to Putnam is the importance of social networks, which reflect the overall structure of small and large societal relationships. This idea comes with some basic assumptions.

Assumptions Underlying the Social Network Perspective

There are a few core theoretical underpinnings to a social network perspective including:

- Actors in a network are assumed to be interdependent rather than independent.

- Relationships are regarded as conduits for the exchange or flow of resources and influence.

- The robustness and structure of a network has influence on the resources that flow to and from an actor and across a network.

- Patterns of relationships present dynamic tensions as these patterns can act as both opportunities and constraints for individual and collective action.

This approach privileges the structure of relationships to hold more sway than the attributes of individual actors. For our work, we start with a structural perspective and then add individual attributes and perspectives. Let’s look a bit more into what a network can illuminate.

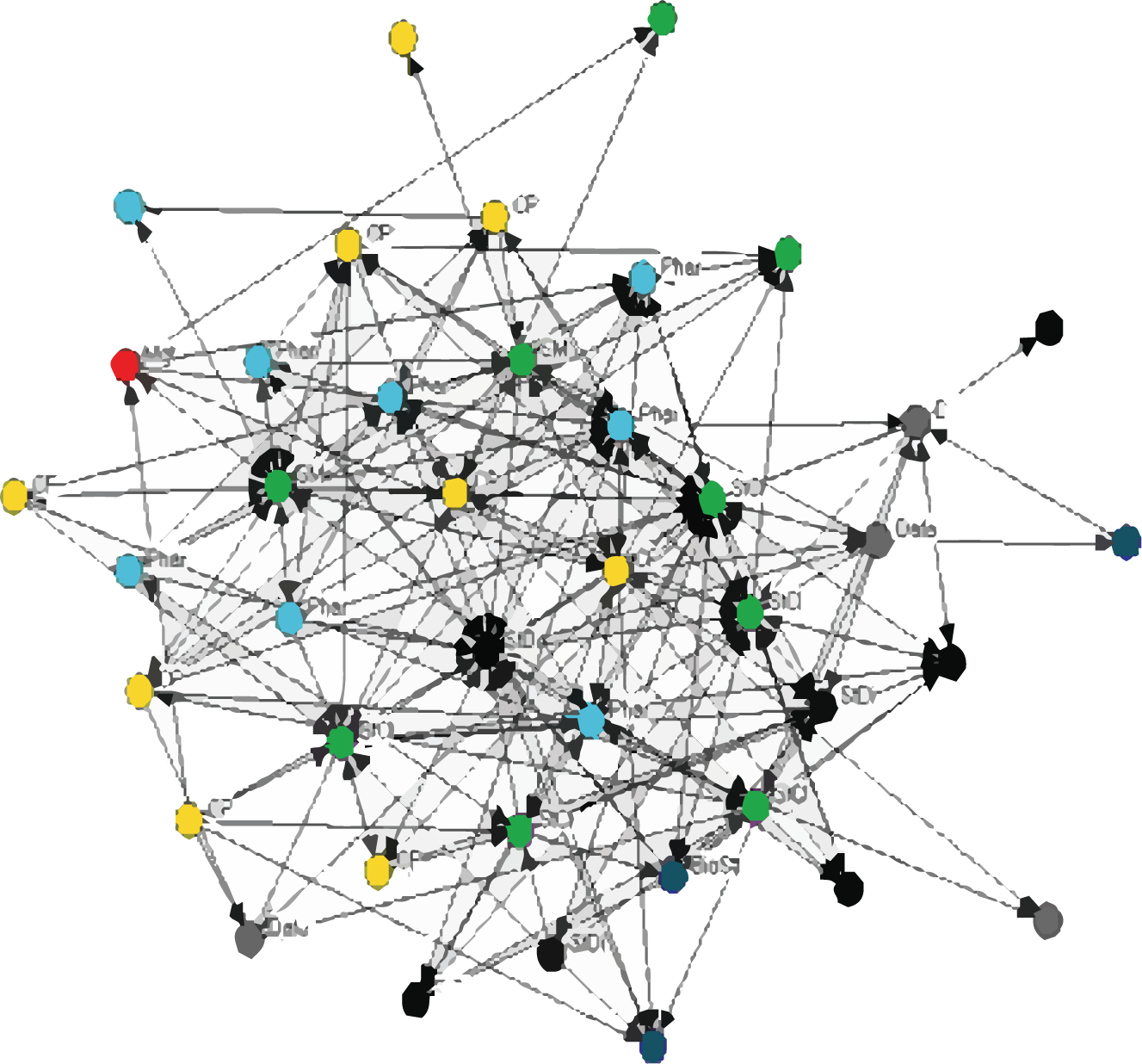

Comparing Formal and Informal Networks

One of the most interesting aspects of social networks is the ability to compare and contrast the formal structure of relationships—meaning how things are formally structured versus how people actually interact. Sometimes, formal professionals are less important in social networks while unofficial individuals are central. In this example, a central player (large red box) in the formal system (left) is at the top of the hierarchy, yet in the informal social structure (right) this actor is marginalized (average-size red dot). Social network analysis can sometimes make the invisible visible.

Networks are Everywhere

Networks are intuitive and show up in many aspects of our lives. They may be structural, like subway systems or computer connections, or social, like relationships with our friends, church members, sports teams, parent groups, or colleagues.

From a social network perspective, individuals or organizations can have relationships that are depicted by lines connecting them, called ties. These ties can be uni-directional (going in one direction or the other) or bi-directional. Ties that go out (i.e. are sent) from one actor to another are called out-ties and ties that come in (i.e. are received) are referred to as in-ties. Ties can sometimes be reciprocated. These can be seen in the informal social structure graphic above.

The size of the circle that represents each individual, called a node, reflects the magnitude of the resource of that individual or group. Some actors have more “importance” in the network, meaning they have more incoming or outgoing ties in comparison to others. Other actors are more peripheral and others are even entirely disconnected from the network (called isolates).

Central Actors

The major actors in a network are considered central because they have more connections than others. These individuals therefore amass disproportionately more resources through unique social links and, therefore, may have undue influence over a network.

Research suggests that these actors also have access to novel and diverse resources, allowing them the possibility to guide, control, and determine the flow of resources to others in a group.6 In this sense, they often disproportionately dominate what information and opinions get moved across a network.

In this project we are most interested in those individuals who occupy a central location in a network, as central actors have been shown to influence other actors and interactions in a social sphere. We are specifically interested in actors who transmit a high number of messages to central actors in the network. We call these individuals transmitters. We are also interested in those actors who both receive and relay a large number of messages to others in the network. We call these individuals transceivers. Both of these types of central actors are important in understanding how resources flow in a network.

Other Actors in the Network

Although our project focuses on central actors, it is also important to consider how those central actors may influence others in the network who are considered more peripheral. More peripheral actors are typically engaged in fewer interactions and, as such, may have limited access to resources and tend to have less influence over the larger network. The perspectives of peripheral or isolated actors may not be as readily spread across a network and information may take longer to make it their way.

References

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6, 68.

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 1360-1380.

- Simmel, G., quoted in Freeman, L.C. (2004). The development of social network analysis: A study in the sociology of science. Vancouver, BC: Empirical Press.

- Moreno, J. L. (1934). Who shall survive? Foundations of sociometry, group psychotherapy and sociodrama. New York: Beacon House.

- Daly, A .J., Finnigan, K, Jordan, S., Moolenaar, N. & Che, J. (2014). Misalignment and perverse incentives: Examining the role of district leaders as brokers in the use of research evidence. Educational Policy, 28(2), 145-174.