The Recent History of Standards Reform in America

The Common Core State Standards in mathematics and English language arts were developed at the behest of the group of organizations led by the National Governors Association (NGA) and the Council Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). The Standards set forth what students should know and be able to do in mathematics and English language arts at each grade level. The development of these standards began in 2009, but they are part of a history of several decades of education reform.

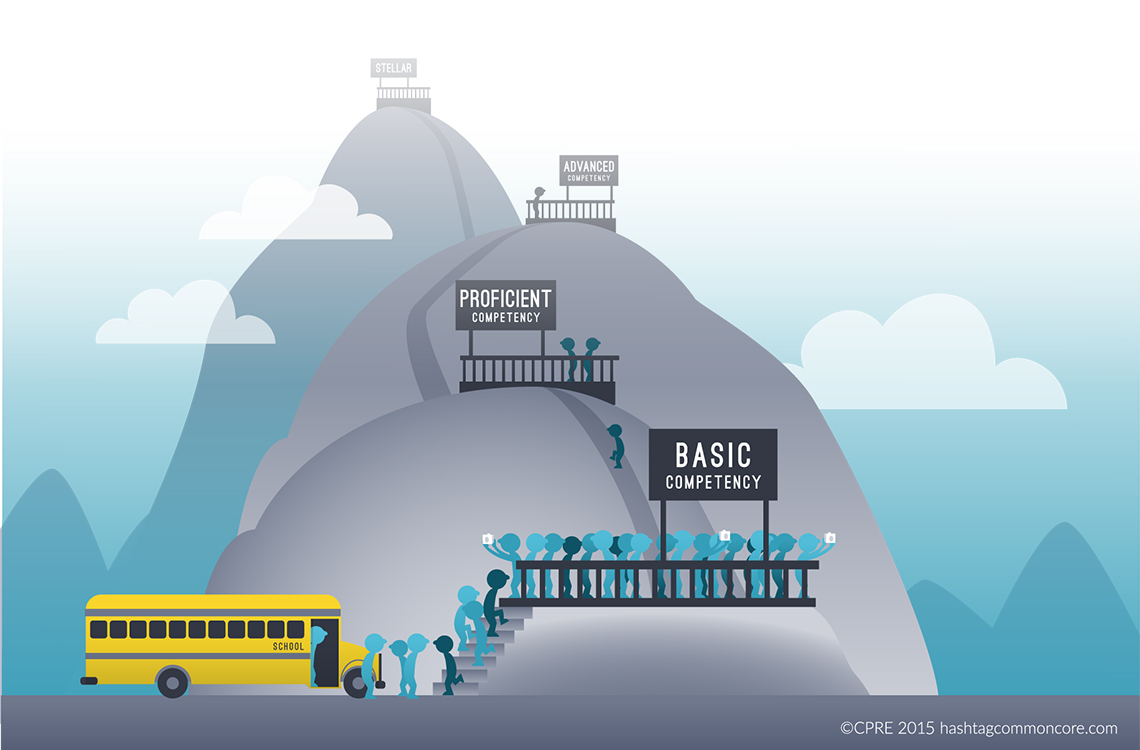

1980s: Focus on Minimum Competency Testing

In the 1980s, policymakers created a set of minimum competency tests, which they intended schools to use as a foundation for performance. The expectations codified in the tests focused on a set of basic skills that schools were expected to have all students meet. However, the basic expectations assessed through the minimum competency tests often became the aspirations for instruction. The important lesson from this era was that low expectations produced low performance.

1990s: Statewide Systemic Reform

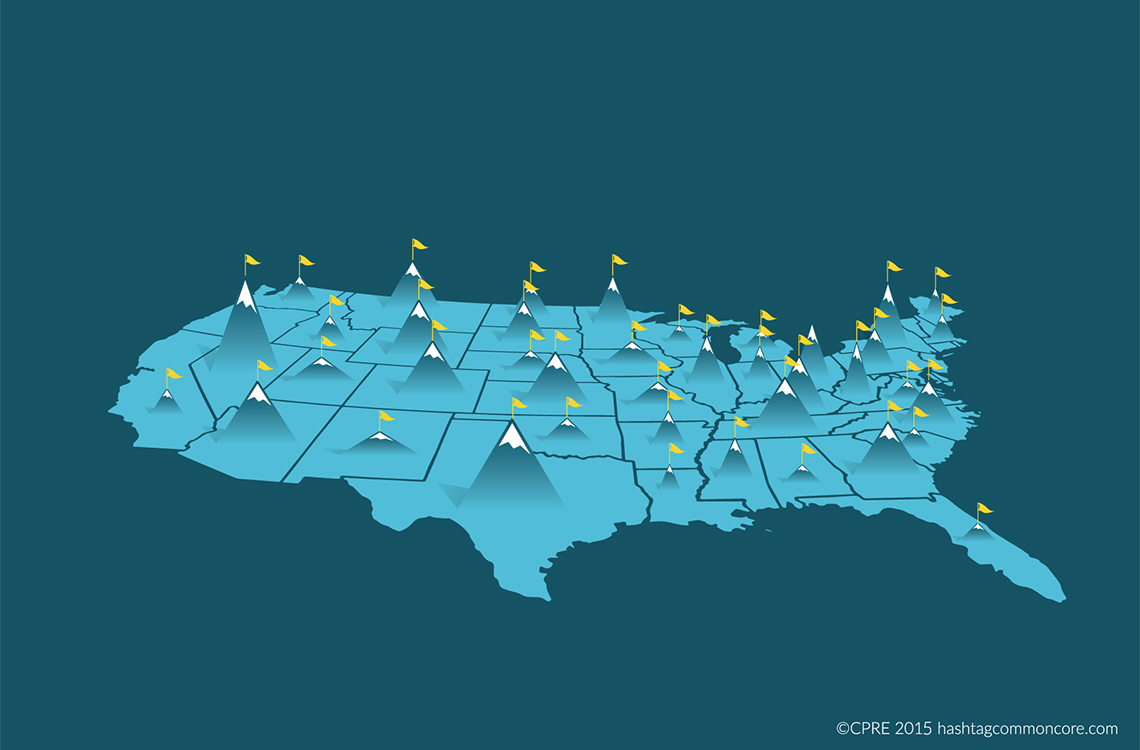

The apparent “race to the bottom” phenomenon spurred by minimum competency testing led to an emphasis on high expectations. The systemic reform effort of the 1990s was built around three general principles. First, ambitious standards developed by each state would provide a set of targets of what students ought to know and be able to do at key grade junctures. Second, states measured progress toward standards by developing aligned assessments that combined rewards and sanctions for holding educators accountable to the standards. The third component was local flexibility in organizing capacity to determine how best to meet the academic expectations.1 This structure of clear goals (standards), measures (assessments), and incentives (accountability) at the state level, combined with implementation autonomy fit with our historical conceptions of education as a local effort. This led each state to develop its own standards and assessment systems, which produced lots of variation in the quality and rigor of state educational systems across the country.

2000s: Test-Based Accountability

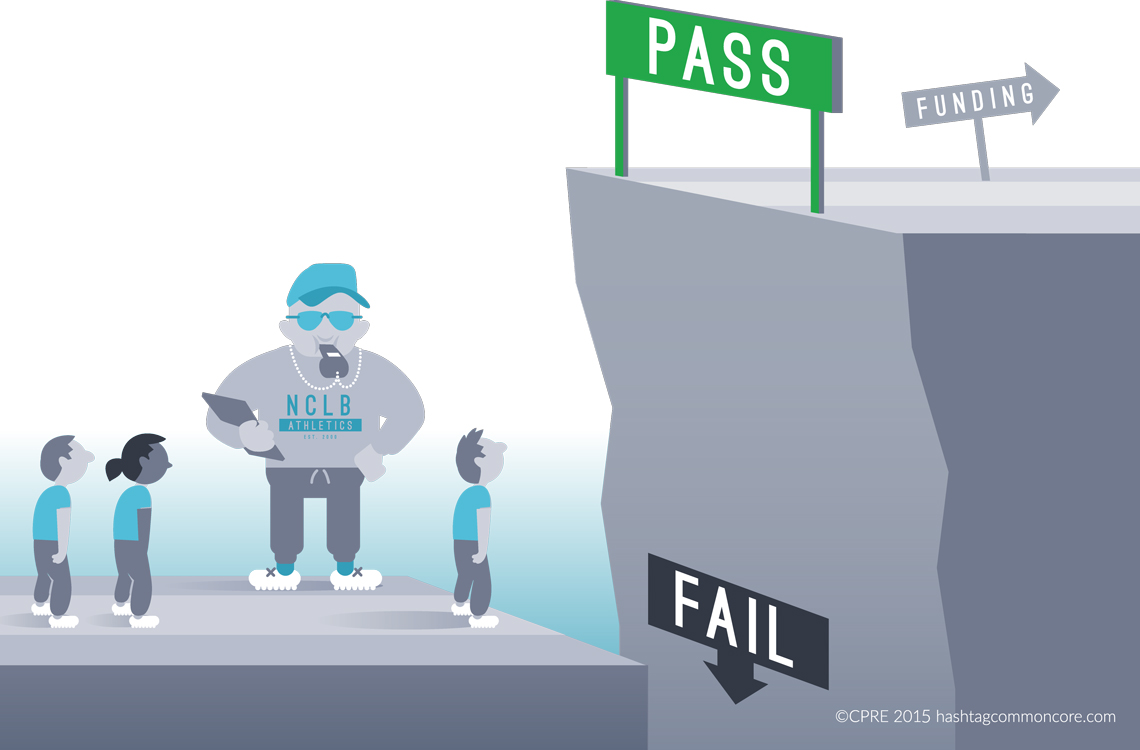

The 2000s gave rise to the era of test-based accountability in education. The 2001 passage of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act inaugurated an expansion of testing by requiring states that received federal funding to assess students in all grades between third and eighth, and one year in high school. NCLB pressed states to develop plans to have all schools make adequate yearly progress with a target of 100% proficiency by 2014—an endeavor that would prove to be impossible. The NCLB legislation also required states to disaggregate school results by subgroups, in an effort to prevent districts and schools from hiding disparities in performance within overall averages. This movement can be seen as an attempt to tighten the linkages in the theory of standards-based reform by increasing student performance expectations via high-stakes testing to hold schools accountable for meeting standards.

Research on schools pressed by test-based accountability showed both productive and unproductive responses. There was an increase in attention to tested subjects, a rise in test preparation behavior, more attention to students just at the cusp of passing the test, and greater attention to heretofore marginalized students.2

Some states also gamed the system by creating tests that most students could easily pass. There were also several cases of systematic cheating by educators in school districts and schools that made national headlines. The accountability emphasis of No Child Left Behind left many policymakers convinced that although pressure was important, we couldn’t just squeeze higher performance out of the system—we had to build a structure to support it.

2010s: “Common Core State Standards”

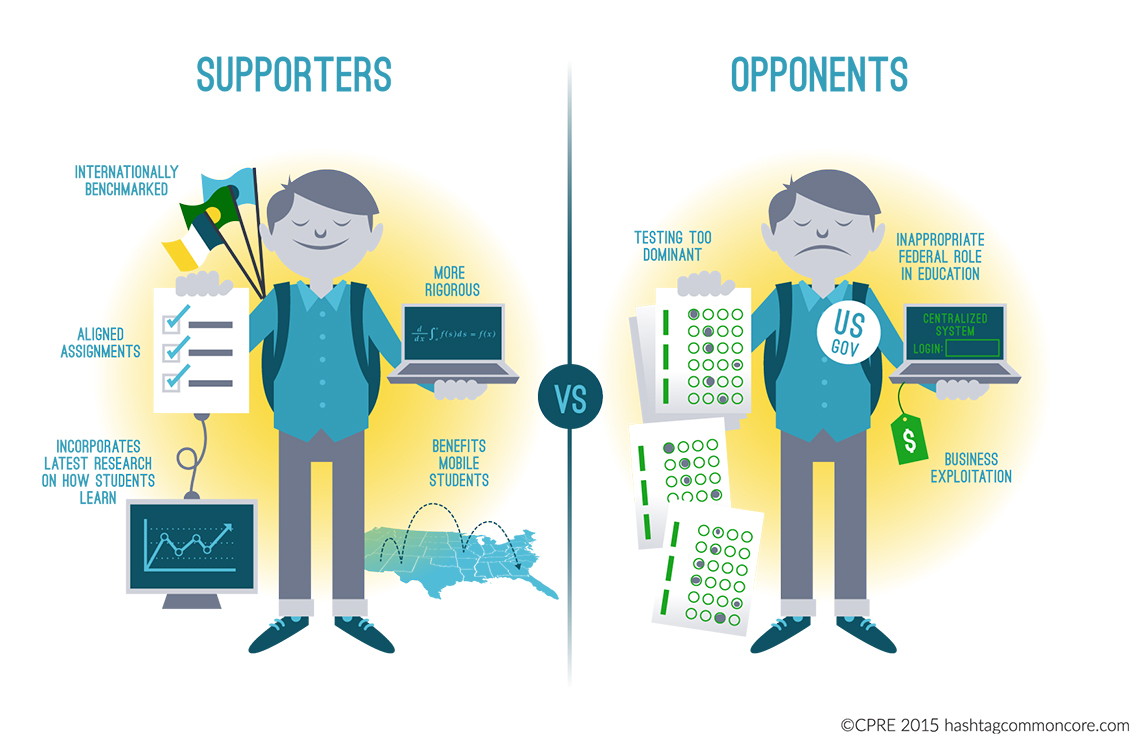

This brings us to the present major reform initiative in the United States - the Common Core State Standards (CCSS). The CCSS set forth what students should know and be able to do in mathematics and English language arts at each grade level from Kindergarten to 12th grade. In a remarkable moment of bi-partisanship, the CCSS were adopted by the legislatures in 46 states and the District of Columbia in 2010. Alaska, Texas, Virginia and Nebraska did not adopt the Common Core, preferring their own state standards. Minnesota adopted the Common Core ELA standards, but not those in mathematics. Since then, the CCSS have become remarkably political and several states have either backed away from the CCSS and/or the associated tests or are in the midst of heated discussions about their involvement with the CCSS.

The CCSS incorporate a number of lessons learned from the earlier standards-based reform movement. The new standards were named the “Common Core” because they were intended to eliminate the variation in the quality of state standards experienced in the past. The experience of the 1990s taught us that not all standards are equal. The new experiment with common state standards was done to avoid the previous problem of differing quality of standards and their accompanying student assessments. —They were developed at the behest of the state governors and chief state school officers to avoid the charge of federal intrusion—which came nonetheless after the Obama administration advocated for standards in the Race to the Top funding competition and provided the financing for the Common Core testing consortia. Similarly, the Common Core testing consortia of Smarter Balanced and Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) were funded to create assessments aligned with the standards. Thus, there was a push for a uniform set of standards and the development of aligned assessments to build a more coherent system for educational improvement.

In sum, many factors led to the development of the Common Core State Standards. Ever since the Nation at Risk Report of 1983, which famously stated "the educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people,” we have felt our education system besieged.3 Flat longitudinal performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) and middling performance on international comparative assessments like TIMSS and PISA has further perpetuated the belief that America needs a more rigorous education system to compete with other nations in the increasingly global economy. This middling performance is often partly attributed to the spiraling nature of what is taught in America’s schools, a student experience that has been called “a mile wide and an inch deep.”4

Thus, the Common Core represents the latest response to the challenge of educational improvement by incorporating the lessons learned from prior experiences with education reform. The minimum competency era taught us that we needed high expectations for all students. The state-wide systemic reform movement of the 1990s taught us that state-led standards and testing systems would produce too much variability in quality and alignment. The decade of experimentation with test-based accountability drove home the lesson that, while accountability pressure was important, we couldn’t just squeeze higher performance out of the system without a coherent infrastructure to support it. All these factors have led to the push for a more comprehensive system with a uniform set of standards and aligned assessments that would allow for consistency in an increasingly mobile society.

References

- Smith, M. S., & O'Day, J. A. (1991). Systemic school reform. In S. H. Fuhrman & B. Malen (Eds.), The politics of curriculum and testing: The 1990 yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (pp. 233-267). New York: Falmer Press.

- Hamilton, L. (2003). Assessment as a policy tool. In Robert Floden, (Ed.) Review of Research in Education, 27, 25-68.

- Gardner, D. P., Larsen, Y. W., Baker, W., & Campbell, A. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Schmidt, W. H., McKnight, C. C., Houang, R. T., Wang, H., Wiley, D. E., Cogan, L. S., & Wolfe, R. G. (2001). Why schools matter: A cross-national comparison of curriculum and learning. The Jossey-Bass Education Series. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.